The Beautiful Darkness

- Patrick Meier

- Nov 11, 2024

- 11 min read

Updated: Dec 5, 2024

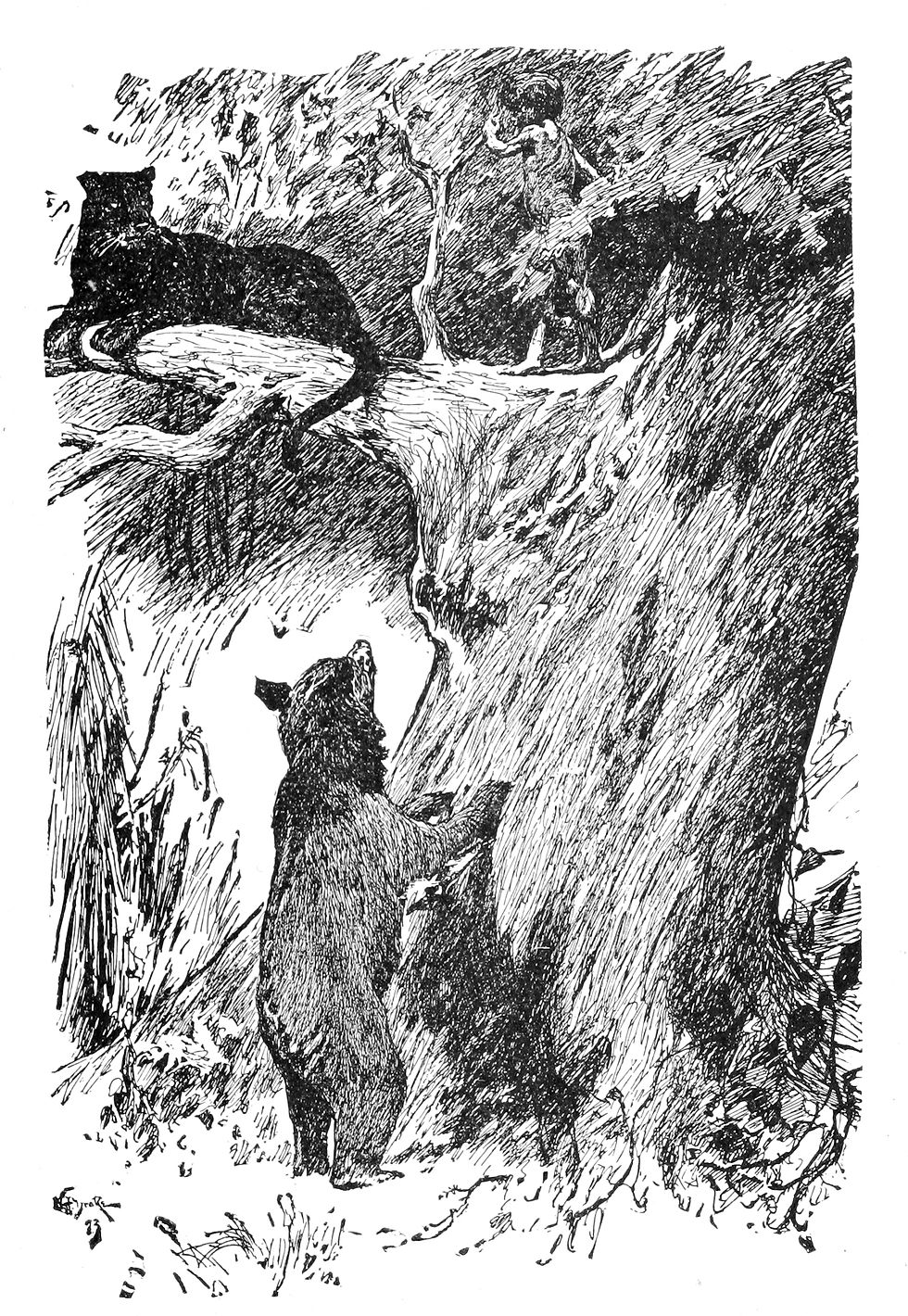

Finding melanistic cats in the wild

As a kid I was fascinated by the books on natural history (and palaeontology, of course) we had at home. There also was a Disney version of Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book I enjoyed. For some reason among all its beautiful characters I was most intrigued by Bagheera, the black panther. It seemed normal that black panthers should live in jungles. But ever actually seeing an Indian jungle, a South American wetland, or an African savannah, let alone encountering a black leopard or jaguar was beyond my wildest dreams.

Years later through my growing interest in natural history, wildlife, and eventually wildlife photography I learned more about melanism in wild felids and started investigating places where black leopards could possibly be found. Fiona Sunquist had published a popular article about melanism in leopards of Taman Negara National Park, peninsular Malaysia, in the National Wildlife Magazine (December 2006).

However, chances for a direct observation in the dense tropical rainforest of Taman Negara would be close to zero. I later travelled twice to this area but had no camera traps back then. Finding a black leopard remained a dream.

Mowgli’s brothers

Now Rann the kite brings home the night,

That Mang the bat sets free.

The herds are shut in byre and hut,

For loosed ‘till dawn are we.

This is the hour of pride and power,

Of talon tusk and claw.

Oh, hear the call! – Good hunting all

That keep the jungle law!

Rudyard Kipling

Before my first wildlife trip to India in 2012 I bought a beautiful vintage hard copy of the Jungle Book. Quite different reading from the safe-for-kids Disney version! Kipling had originally set this tale in Rajasthan, an area he knew well. However, before publication he moved the site to the Seoni hills, in central India, now Madhya Pradesh bordering Maharashtra. Kipling had never visited Seoni but knew about it from family or friends who had travelled there. The description of the jungle best seems to fit what is known today as Pench National Park and the Pench River, albeit in the book Kipling writes about the Wainganga River, which flows a few kilometers east of Pench.

As it happened, Pench, along with Kanha, and Gir Forest National Park, were on the itinerary of my first visit to India. In hindsight, this three-week excursion in April 2012 with focus on tigers and Asiatic lions provided some beautiful wildlife encounters. But finding, let alone observing and meaningfully photographing wildlife in the dense forests on the subcontinent can be challenging, to put it mildly. I saw one tiger, but no leopards in Pench. After this trip, the dream of encountering a melanistic leopard moved to the back of my mind.

The Rise of Saaya

Sometime in 2016 the first stunning photographs of a male black leopard in Kabini Tiger Reserve (Nagarhole National Park) appeared in social media. I asked Malini about travelling there. After all she had grown up in Bangalore and had worked as a naturalist and guide in Bandipur National Park adjoining Kabini. Malini and her parents knew the place and the people managing the park well. The answer was clear: “Don’t go there! Kabini River Lodge as the only place organising safari drives and wildlife-viewing in general are state-organised, and the whole process of searching for wildlife in Kabini cannot be compared with anything we do in other parts of the world. You will end up with 30 passengers in a noisy old minibus on main tracks in the forest amid dozens of other vehicles.”

Although I could hardly imagine this to be the case, we put it off for a while, but soon new material was published: this time captured by Indian photographers Mithun Hunugund and Shaaz Jung. I wanted to give it a try and in June 2018 we first became part of the incredibly frustrating organisation required to access Kabini*.

*This, however, is a story for another time which I will want to note not as an endless list of complaints, but as a respectfully well-meant concept of what could be, if ever the people in charge wanted to improve visitor experience, ecological impact, and economic results of the way India’s national parks are accessed.

By 2018 Saaya, which translates to “shadow” in Hindi, had firmly established his territory in an area of Kabini that was partially accessible to visitors. Based on the time I spent in the park I reckon the cat’s range probably covered around 25km2 – 30km2. Due to relatively high prey density, it didn’t need to be larger than that, extending to the east towards the territory of a leopard known as Scar face and to the west across the Bar Balle, a seasonal stream across of which lies a section of the National Park that is not accessible to visitors.

During the time when Saaya lived in his biological prime between 2018 and 2022, I spent over 50 days, or more than 450hrs searching for this animal in Kabini. There were numerous occasions where I had missed Saaya by minutes, even seconds. Typically, we would be waiting at an intersection, listening for alarm calls in the forest, when our guide would receive a text message and immediately drive to the site where the black leopard had been seen. When we reached a few moments later, the forest was full of alarm calls from chital, sambar, barking deer, langurs, peacocks, and many other bird species, but the cat had vanished.

I include a little "behind the scenes" gallery of my time exploring Kabini. Particular highlights included getting caught in violent storms that blew over trees next to our vehicle, getting stuck on the power line road and having to convince the other passengers to get off the vehicle to help push, getting stuck again behind the minibus that couldn't get past the road building machinery, several female leopards also looking for Saaya, and the potentially stunning forest scenery, if it wasn't for floods of invasive plants. And of course the wait twice daily at JLR for the vehicle to which we would be assigned for the next drive.

As fair compensation I enjoyed some special-to-spectacular sightings of India’s wildlife and learned a lot about the seasonal dynamics of Nagarhole National Park. There are several other places in India where melanistic leopards occur and high-level planning for future trips include the Western Ghats and areas in north-east India.

Aberdare National Park, Kenya

The next attempt at finding a black leopard with the additional option of possibly also finding black servals took Malini and me to the Aberdare National Park in Kenya. This relatively small park about 100km north of Nairobi covers an area of 767km2 and lies between 2’000 and 4’000m above sea level. A first stay at The Ark near Nyeri in 2017 provided the insight that exploring the high plateau where sightings of melanistic cats have been reported would require staying over up there. Our friend Shaun Mousley, owner of Nomadic Africa Safaris arranged our second stay in January 2019 at the self-catering accommodation which is provided by Kenya Wildlife Service. These cottages are located at about 2’800m above sea level. Temperatures dropped to -5° C. every night, while afternoon temperatures remained around 20° C. The high plateau is largely covered by dense shrubs. There are some gorgeous stands of lichen-decorated forests, open grassland, and bamboo forests. It is clear why such dense, dark vegetation would not create a disadvantage for melanistic predators.

Some impressions from the Aberdares: a yellow serval patrols along a road, impressions of the dense vegetation of the high elevation areas, finally a melanistic leopard on camera trap, a melanistic small-spotted genet, and ready to take off by helicopter to fly to Laikipia.

The use of camera traps is permitted, but there are elephants, buffalo, and hyenas around. Setting up and maintaining traps requires caution and the devices are potentially exposed to damage by animals.

About a month before we embarked on the trip to Kenya, spectacular camera trap photographs of a black leopard from yet another area were circulated in social media. These photographs had been made in the garden of a private home in Laikipia. Not too far from the Aberdares as the crow flies, but certainly a full day’s driving in either direction from the Fishing cottages. We discussed the options with Shaun and he contacted the owner of the private home. After a while we received permission to set up traps for 10 days but needed to find a suitable arrangement for our transfer from the Aberdares to Laikipia, and back again. With the road too long and no airfield open on the plateau, the answer came in form of a helicopter transfer. This meant that we would set up 5 traps in the Aberdares and 4 in Laikipia, then spend our field time in the Aberdares, but change the itinerary to have two nights at Laikipia Wilderness camp at the end of this trip.

The photographic results were meager: no luck with leopards in Aberdare National Park, but one melanistic serval on a trap. One ok-ish photo of the gorgeous young black male leopard in Laikipia. All trap sites had suffered from the poor performance of our camera trap gear. Endless false-positive detections filling cards and depleting flash batteries. – This experience would eventually result in the founding of Intellitraps Ltd.

Laikipia Wilderness and Loisaba

In 2021 we ventured again to Laikipia and Loisaba. At Laikipia Wilderness we intensified our search for a yellow female leopard that had been seen near Laikipia Wilderness Camp leading a black cub. We didn’t find the cub, but at least this time there were direct observations of two individuals in different areas, albeit not resulting in photographic opportunities. Early functional models of Intellitraps camera trap sensors had been set up at Laikipia Wilderness, at the neighbouring Mpala Research Ranch, and later at Loisaba Conservancy. the 17 field days again provided great wildlife encounters, and the test results for Intellitraps were impressive and important. The opportunity of finding a black leopard just didn’t present itself.

Behind the scenes of earlier attempts in Laikipia: Lenguya helping us to find camera trap sites near Mpala Ranch, followed by unseasonal extreme downpours resulting in one of the early Intellitraps functional models getting drowned (but surviving the ordeal), setting up the trap near the carcass of an unfortunate cow, more wildlife and camera trap impressions, and eventually a black shadow at midnight across the Ewaso Narok River.

Then, in 2023 a young black female started to appear on her own in the area around Laikipia Wilderness Camp. The cub had survived to adulthood! At first this leopard shared her mother’s territory, then carved out her own, partially on Laikipia Wilderness’ land, and partially across the Ewaso Narok river on Suyian Conservancy. As October 2023 saw a safari in Zimbabwe come up for Malini and me, we arranged a return to Laikipia Wilderness in January 2024. By now, sighting reports of “Giza Mrembo”, the Beautiful Darkness had become solid as this young female started to feel comfortable around safari vehicles looking for her and following her through the bush.

January 2024

The excursion started not without challenges. Laikipia Wilderness Camp could only offer us a tent for 7 nights. Our flight from Nairobi Wilson airport to Loisaba airstrip departed from a wet runway. As we approached Mount Kenya, the pilot of our Cessna 208 Grand Caravan told us that he would have to stop at Nanyuki as low cloud cover currently prevented approaching Loisaba. By now conditions were very wet. However, the pilot decided to have ago at it as the clouds cleared a bit and we safely made it to Loisaba airfield.

I knew that the shortcut via Luisa’s Crossing would not be open. Instead, the transfer would require a good two-hour drive along the escarpment, then down a steep muddy path to the high bridge across the Ewaso Narok, and from there all the way downstream to Camp.

After lunch we got the cameras ready and agreed with our guide Steven to place a scout equipped with binoculars and a two-way radio on a hill nearby while we would head out by vehicle along the river to search for tracks.

The call came soon. Giza Mrembo was approaching the river from the opposite shore. I could hear alarm calls from birds, and eventually see the rather excited birds looking at a predator moving through tall grass. Moments later the black leopard appeared on a granite boulder about 200m from us, stood still for a moment observing the fast-flowing river. I just sat there with my mouth open. The size and shape, the glittering black coat, piercing yellow eyes, the sheer elegance… it took a moment to understand that preparedness and determination had finally met opportunity:

In the days that followed it felt like all the luck I didn’t have since the beginning of this search now came to me in one go. The black leopard showed up on six of our seven days at Laikipia Wilderness and initial safety shots were completed with more and more scenes of behaviour, day and night, peaking in the successful hunt of a Kirk’s dikdik, its lifeless body being dragged back across the river to prevent having it stolen by one of the male leopards frequently following Giza Mrembo around.

As I sat there on the Toyota Land Cruiser that had especially been prepared for photography, words which Russell MacLaughlin told me in Kabini during the June 2018 excursion came to my mind:

“Better prepare yourself. This is the most beautiful animal I have ever seen.”

In total I have so far spent more than 90 days, or 800hrs in the field for this. Although I am yet to encounter Bagheera of the Indian jungles, the portfolio I managed to compile from the seven days at Laikipia in January 2024 show the realisation of a great personal dream!

About melanism in wild felids

Of the 40 wild-living cat species, 13 can develop melanistic coat coloration. In the Panthera lineage this affects leopards and jaguars. Melanism in felids is caused by a genetic mutation: an interaction between two genes which regulate the production of melanin, a pigment that gives colour to skin, hair, and eyes. It is an excess of dark pigmentation which makes a mammal, bird, or insect look dark while maintaining baseline coat or feather patterns. There are two forms of melanism; true melanism and pseudo melanism. Both conditions are hereditary but are not always exhibited as they can skip generations. True melanism occurs in jaguars, leopards, servals, kodkods and Geoffroy’s cats, while pseudo melanism may affect tigers, cheetahs, and Bornean bay cats.

Although the leopard seems to be fully black, on closer inspection and in direct sunlight, the rosettes of its coat pattern are still evident. It is a recessive character that appears to be strongly influenced by natural selection. Individuals living in environments where this dark morph is advantageous in camouflaging and for thermoregulation, are found in habitats such as rainforests and the distinctive subalpine grasslands typical of the mountains of East Africa. In some ecosystems like those of southern Thailand and peninsular Malaysia, the incidence of black leopards is very high reaching almost 70%, indicating the importance of the colour of the animal for its survival. Interestingly, not all leopard sub-species show this trait: so far only five of the eight recognised sub-species have confirmed melanistic individuals.

How do black leopards end up in the dry savannah of Laikipia?

I have been wondering about this for some time. Extensive discussions around campfires lead to the red wine infused non-scientific theory that the presence of melanistic cats in the Aberdare mountains and around Mount Kenya literally is the source of this phenomenon: water from north-facing shoulders of these mountain ranges flows to Laikipia. The Ewaso Narok from the Aberdares and Dundori Ridge, the Ewaso Ng’iro from Mount Kenya, merging at the Junction to drain into the Ewaso Ng’iro lowland subbasin). Over time, melanistic leopards dispersing along the water flow would have eventually reached Laikipia.

Historically, this water would have flown north-east to what today is Somalian territory and reach the Indian Ocean north where the town of Kismaayo is now located. However, as far as I have been informed, in current-day climatic conditions, the water never reaches the ocean but evaporates and seeps away somewhere downstream on its way to Somalia along the border of Kenya’s desertic Wajir and Garissa Counties.

This means that the Laikipia Plateau may represent a globally unique position in that its vegetation consists of dry savannah and grasslands, yet it also has melanistic leopards that would usually be present in dark, dense vegetation only where the animals would be very difficult to spot.

Writing these lines makes me want to return to Laikipia... let's make a plan!

Patrick Meier, November 2024

Comments